Casey is considering taking his first management position at a Series B round company entering a growth phase. He just finished a stint at a small startup which was acquired and hadn’t grown enough to need managers. Casey hasn’t been a manager before so he’ll be a new manager. He also hasn’t been exposed to many experienced managers. He framed his question beautifully :

“What would I do all day as a new manager?”

This is such a great question. The shift into front-line management is one of the hardest because it’s about finding the balance between “doing” and “managing”. More new managers fall at this hurdle than any other. Either the new manager completely steps back and does nothing but manage people, which can breed resentment in the team and leaves important work not done. Or the new manager cannot step away from the “doing” that made them successful, and doesn’t do any management so the team falters.

So how to explain what a new manager does?

The History of Managers

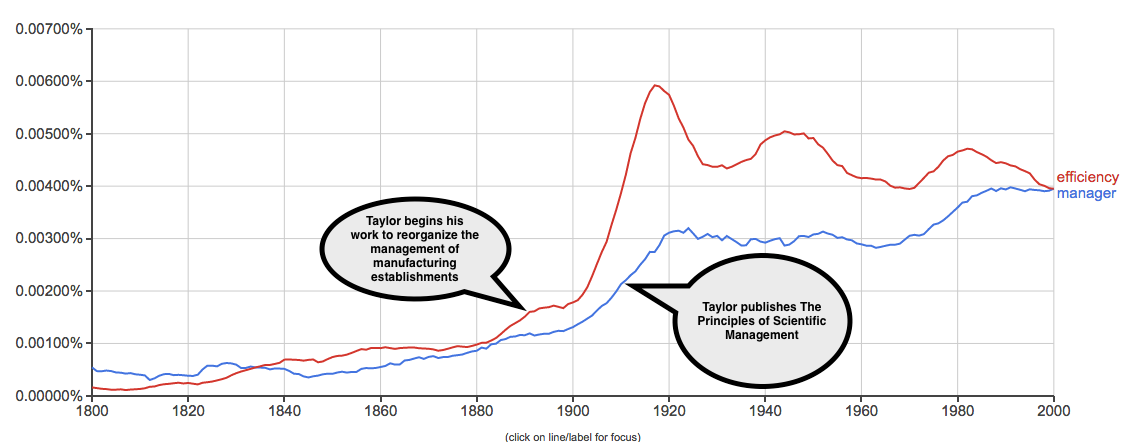

I find it helpful to go back into history and a gentleman called Frederick Winslow Taylor for the answer. Born in Philadelphia in 1856, Frederick Winslow Taylor was a mechanical engineer who became obsessed with maximizing output of the Midvale Steel Company factory. He believed that by using scientific methods – measurement and analysis – you could improve output and profitability. Taylor’s breakthrough was tying that measurement and analysis to individual employees and offer financial incentives for improved output. We now call this pay-for-performance. In his book Principles of Scientific Management, Taylor describes an interaction between him and an employee called Schmidt who is encouraged to increase his output from 12.5 tonnes of pig iron in a day to 47 tonnes in exchange for 60% higher pay.

Taylor created managers, efficiency and pay-for-performance. This Google N-Gram shows how the words efficiency and manager exploded in usage after Taylor published Principles of Scientific Management.

Managing In Taylor’s Factory

Managing in Taylor’s factory required a broad set of skills.

- You need to know what your factory produces

- You had to have a good working understanding of the different parts of the factory

- You had to understand how the different parts of the factory worked together to achieve the end result

- You had to be able to motivate your workers to do their jobs

- You had to set goals and measure how the factory and the individuals performed against them

- You had to look for opportunities to improve the flow and output of the factory, and have the courage to put them into action

This is a simple framework to explain what a manager does. Casey is considering a job managing a business development team. His “factory” takes contact details and turns them into paying accounts (1). He needs to understand how his team develops accounts (2). He has to learn how each member of the team participates in developing accounts (3) and how to motivate them (4). He has a goal he has to meet in terms of revenue (1), and he has to set and track goals for each member of the team (5). And as he’s building up his understanding of his business development factory, he will be looking for ways that the factory can be improved and be more profitable (6).

Filling Your Days As A New Manager

This model describes the type of things Casey might do, but isn’t illustrative of how he might spend his time. Casey’s job would have 8 direct reports. This is a lot for a new manager. Let’s assume Casey works a standard 40 hour work week. It might break down like this :

- Weekly 1:1s with each of you team member (8×1 hours) = 8 hours

- Weekly team meeting and preparation = 2 hours

- 1:1 with manager and prep = 2 hours

- Meetings other people schedule that you need to attend = 4 hours

- Tracking and processing metrics / data = 2 hours

- e-mail = 4 hours (if you’re disciplined!)

- Networking with your peers and management chain = 3 hours

- Participating in customer calls = 4 hours

- Ad-hoc discussions with your team members = 5 hours

I’d call that the recurring, weekly work. That leaves about 6 hours for thinking about the important stuff like initiatives and ideas to drive the team, improve performance etc. The takeaway here is that you need to aggressively prioritize what you spend your time on, which usually means choosing what you’re NOT going to do.

One More Question

Having processed all this, Casey had one more important question that every first time manager should ask.

How do I become a good manager?

This is a question with endless answers. I’ve seen a lot of new managers try to be someone else, or in fact try to “act” like a manager. The simplest answer to this question is to be you. If you’re a helpful and thoughtful person, be a helpful and thoughtful manager. If you’re a detail driven person, be a detail driven manager. The trick is to be aware of what those traits and habits look like when they don’t serve you. I think of Casey as someone who puts a lot of effort into showing up and supporting his team mates. So the pertinent questions for him are : will you be able to show up at the same level / intensity in this new role? How will you reconcile your desire to support people with your need to hold them accountable for results? If Casey can get a handle on that, I’m confident he’ll go on to be a great manager.